Blockchain overview: introduction

Structure

For many, blockchain and Bitcoin are interchangeable synonyms. In this series of posts, I argue that world of blockchains is much more complicated than that. I plan to describe features of several popular platforms with emphasis on performance and scaling solutions. This article is an introduction to the subject.

Motivation

My recent involvement in local startup gave me great opportunity to dig into blockchain technology. Nowadays blockchain is buzz-word and Internet generate a huge amount of content about cryptocurrencies, smart contracts, and a blockchain scalability problem. People talk a lot about the usage of blockchains and challenges of its wide adoption. Sadly enough, I don’t see enough technical content which compares existing and emerging solutions from the technical point of view. Such article would be useful to me 3 months ago and I am going to approach this gap.

When I started in a blockchain developer role I didn’t know much about altcoins (alternatives to Bitcoin). Job description clearly stated that their main requirement was Bitcoin knowledge so I easily passed an interview. It appeared that my new coworkers weren’t interested in altcoins at all. They believed that all altcoins are Bitcoin forks and forks don’t bring anything useful into this world (which is strange because they were developing altcoin by themselves).

I wasn’t sharing the same view on altcoins so I decided to dig by myself and to understand main innovations of most popular platforms. It appeared to be a time-consuming task because there are a lot of solutions and many of them differentiate from others by some technical innovation. After glancing at a dozen of whitepapers, and googling I developed a small blockchain cheat sheet for myself. I decided to present it in a readable form with the hope that it will be useful for others.

Blockchain definition

What is blockchain? Instead of a scientific definition, I use my own intuitive version. The blockchain is a distributed application which works in the huge untrusted network where some parties can act maliciously for their own sake. This definition is not self-sufficient because “application” is vague term but we will discuss it later. For now, really important parts here are “distributed in the huge untrusted network” and “act maliciously”. I believe these two phrases describe innovation of blockchain.

Who will “act maliciously”

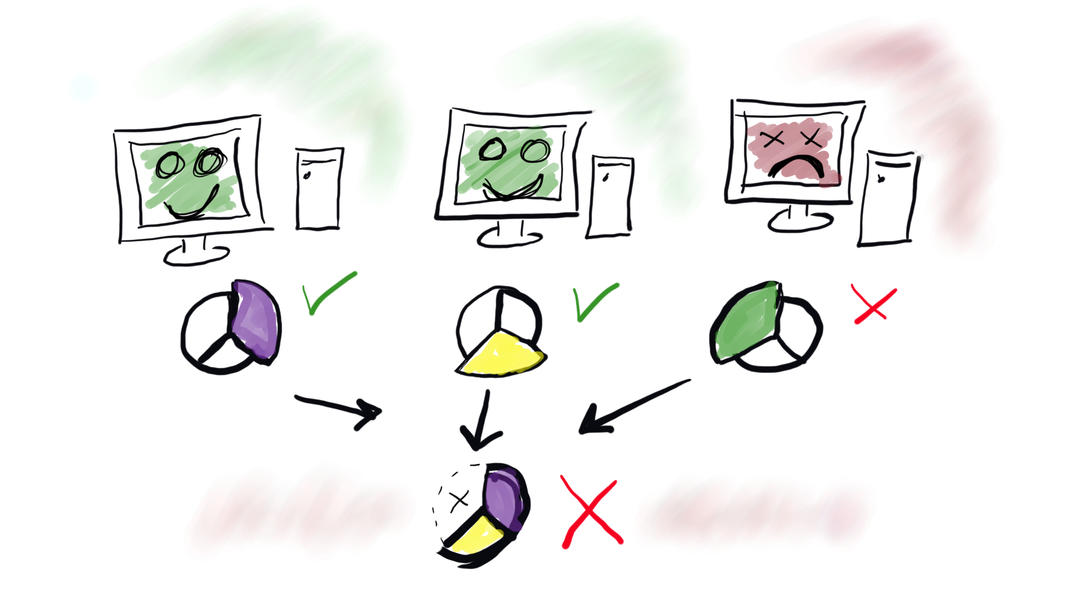

Blockchain should tolerate Byzantine failures. Byzantine failure is when part of distributed system misbehaves in some way other than just stopping working (probably in some intelligent way). Below is more friendly decryption of what is a Byzantine failure.

Let’s consider few examples of systems distributed across several network nodes (which are not blockchains).

First one is a database with sharding. You install the same instance of the database server on several nodes and split dataset between them (here we assume no redundancy, all nodes have different not intersecting parts of data). If one node fails then your whole distributed service becomes malfunctioned since it can’t serve data from the failed node. This is distributed system which can’t tolerate any node failures.

The second example is a database with replication. You install the same instance of the database server on several nodes and copy (replicate) same data on those nodes. If one node stops serving requests: no problem, other nodes will serve same content. This distributed system can survive node failures when a node stops functioning (this is stop failure). But what happens if due to some weird data corruption or due to hacker activity one of the nodes starts serving wrong data. In this case, node didn’t stop serving requests but failed by giving wrong results or by violating communication protocols. Literature calls such fails Byzantine failures. Obviously, in case of Byzantine failure, some of your replicated database clients will obtain wrong results so the whole system becomes malfunctioned. And we can conclude that such database with replication is an example of a distributed system which can tolerate stop (simple) failures but can’t tolerate Byzantine (complicated) failures.

The third example is from mission-critical embedded systems. You design a crash detector for a car. And you know that in some very very rare cases crash sensors can misbehave by producing wrong results. Sensors don’t stop working, they just give wrong answers. So you decided to install three sensors instead of one and run them in parallel. With 3 sensors working in parallel you can detect failure of the single sensor and still can figure out right answer by a using most popular among sensors answer. This system can tolerate Byzantine failures (it will work correctly if up to 1/3 of nodes fail).

Algorithms for Byzantine fault tolerance were invented long before the invention of Bitcoin. Byzantine fault tolerance is not something completely new in computer science and in the industry (DLS, PFBT).

Why “distributed in huge untrusted network” part matters

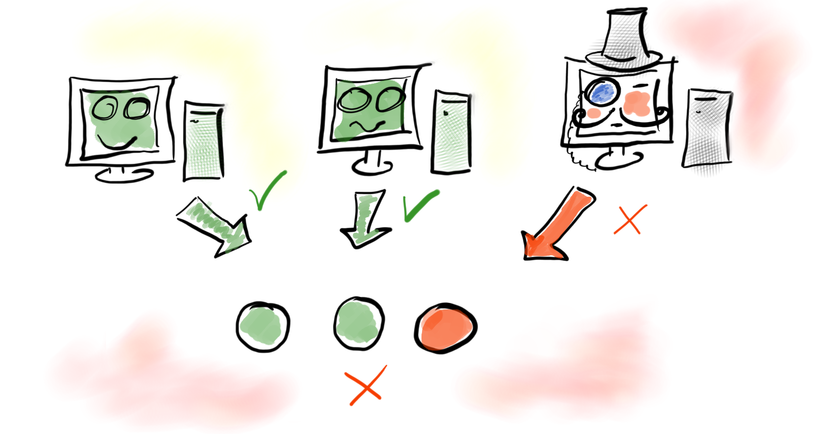

Here for simplicity, we talk about Bitcoin. It runs on the Internet and there are the huge amount of Bitcoin nodes in different parts of the World (tens of thousands). The core feature of Bitcoin is that absolutely anyone can join the network. And no one can guarantee that arbitrary person who joins network will run the trusted software. Most people run the client from Bitcoin developers, but some of them run alternative client written in golang, and some of them can run their own version of a client. And their custom version of a client can misbehave in some intelligent way. Moreover, malicious users can try to deploy a number of malicious nodes and coordinate their behavior.

Bitcoin can tolerate coordinated attacks as long as a majority of the network is healthy (see Ghost protocol introduction for simple explanation). There were algorithms which can tolerate Byzantine failures in the untrusted network prior to Bitcoin invention. But they don’t scale to a massive network. So Byzantine fault tolerance in Internet scale is true innovation from Bitcoin. Nowadays people figured out how to apply those “classic” byzantine fault tolerance algorithms to build blockchain (see Tendermit), but 10 years ago Bitcoin was true innovation in this problem.

Model for blockchain

I use a simple model to talk about blockchain. It is mostly inspired by Ethereum wiki which talks a lot about state and state transformations.

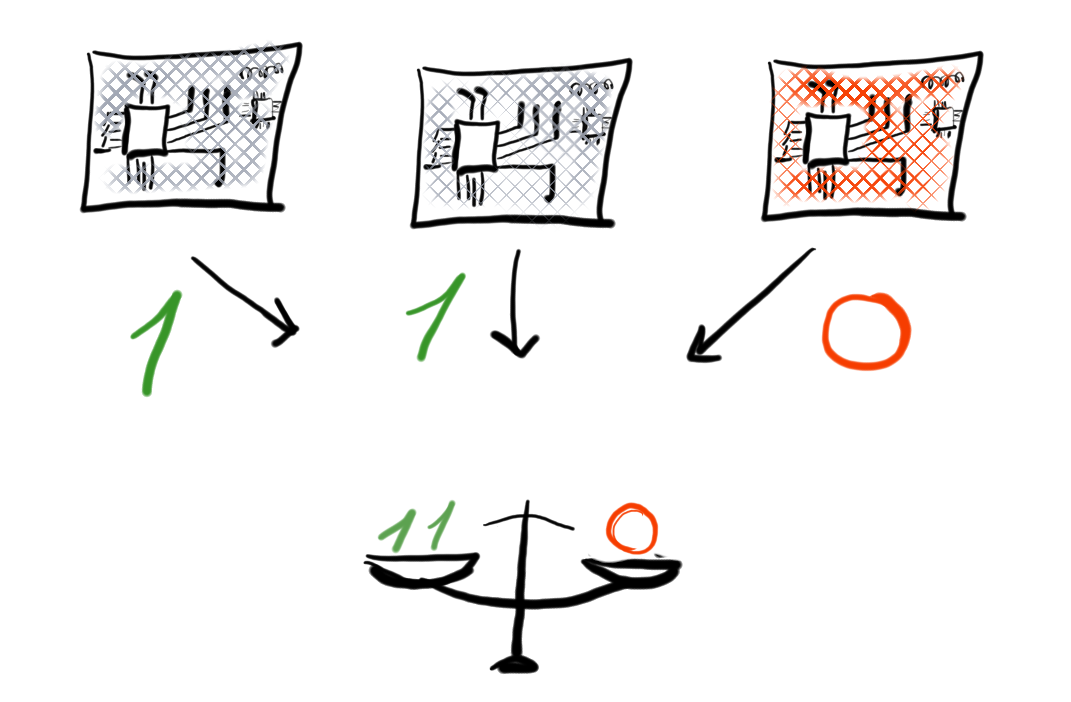

Blockchain consists of 3 parts:

- State.

- State transformations.

- Consensus

Also, there is 4rth hidden part in this list: (4) communication between nodes. Nodes communicate to gain consensus and to change state. I didn’t add it explicitly because I think that distributed nature of blockchain assumes p2p communication between nodes.

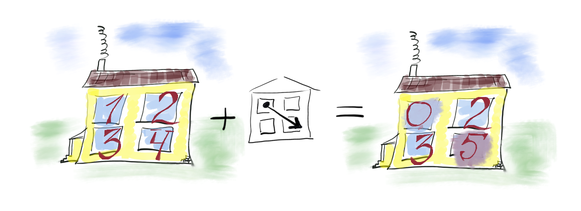

Let’s talk more about this model using digital currency as an example. Digital currency should have accounts and each account should have its balance. List of all accounts and corresponding balances is a current state of the currency.

State transformations are transactions. A transaction is a transfer of money from one account to another which changes balances and state.

Here I want to make one important remark. State + State Transformation is a useful model for many applications. If we also add “Representation” to this pair then we will end up with State + Representation + State Transformation which is essentially Model View Controller. Model View Controller is a model useful to talk about almost any application and it has been dominating paradigm for web applications for a long time. By using only State + State Transformation part you obtain Model + Controller. With these two you can easily talk about any server-side application. You can think of the State as your database. State transformations are your business logic. I made this remark to give you understanding that blockchain is useful not only for digital currency but also for many other applications.

The consensus is what turns ordinary Database + Business Logic application into popular Rocket Ship bleeding edge science sexy buzzy hipster application. It works like this: users of the p2p network send requests for transforming state to their peers (they send transactions in case of digital currency). Those requests spread across the network and at some point consensus algorithm comes into play. Nodes have to decide which requests are valid. They also need to decide in which order to apply requests (true for a system where order matters). The ultimate goal of consensus algorithms is to make sure that at any point in time whole p2p network has the same view (copy) of the state. This is too hard (or even impossible) to achieve in practice so nodes in the p2p network maintain history of state transitions. Most recent history can differ among different nodes but older history always same between all nodes. History stabilizes with time and consensus algorithm needs time to reach reliable consensus.

Later we will explore blockchains where All 3 components of discussed model differ.

Notes about distributed communication

Every respectful talk about distributed systems refers to

- The CAP theorem.

- The FLP impossibility result.

Chapter 2 of Distributed systems for fun and profit book talks about these theorems in very friendly language.

My intuition for these theorems is following:

-

There is design trade-off: in case of networking disaster system stays either consistent or available. Alternatively, it chooses behavior which is somewhere in the middle between two. The complete description is below.

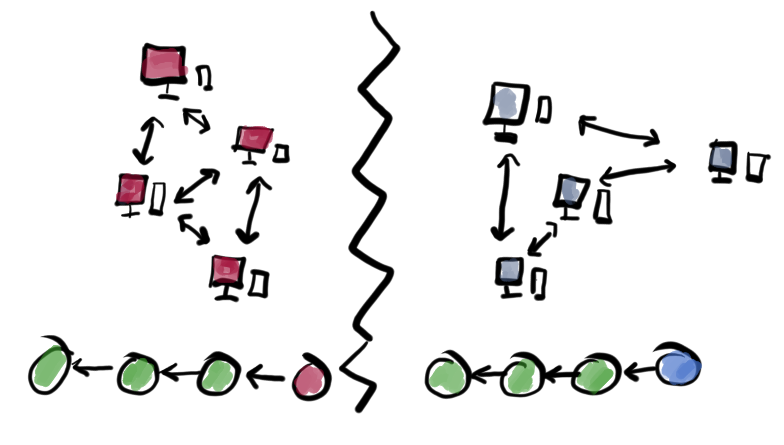

If p2p network is divided into isolated parts (aka partitions) then system has two choices.

-

It can forbid state transformations to prevent state divergence between isolated parts of the p2p system. Such systems prefer consistency over availability. They stop the usual way of functioning or in other words, they become unavailable.

-

System can continue functioning which means each isolated part continues working on its own. Systems stay available but it is no longer consistent: isolated parts have no chance to coordinate state transformations and hence they maintain different versions of reality. Such systems prefer availability over consistency.

-

-

The Byzantine generals problem(*) has no solution under strict assumptions. However, it has a practical solution which works well but not ideally. Proof Of Work is an example of a practical solution which works well in practice but not perfectly. Forks in Bitcoin network is an example of such imperfection, we will discuss it soon.

(*) The Byzantine generals problem - several parties try to reliably agree on some fact over an unreliable network. For example, 3 computers try to choose a single number by using the network. This should be solved in such way that each computer knows for sure that other 2 computers chose the same number. The most difficult part here is “you know that I know that you know that I know ...” reasoning which doesn’t terminate unless we ignore some probability of failure. In practice, however, networks can be described statistically and they have a low probability of failure. So at some point, we can decide to ignore 0.0000...0001% chance of failure. And also we can use the notion of time and introduce timeouts which don’t change anything from the theoretical point of view but work in practice.

To be continued

- We have defined what blockchain is.

- We have briefly covered challenges of distributed systems (consistency vs availability, Byzantine failures, distributed consensus).

- We have produced simple model which will help us to classify and discuss many of existing blockchains (state, state transformations, consensus).

See you in next posts which will describe Bitcoin, Ethereum, different altcoins and the blockchain scalability problem.

Thanks

Many thanks to Lena V. and other friends who gave me feedback. After your response, I’ve decided to factor out Bitcoin and Ethereum into separate self-sufficient posts.

Thank you for reading, if you have spare minute, please give me some feedback. I write just for fun and knowing that the result of my work is useful will bring me more fun.